We Need to Read Our Textbooks—Really Read Them

November 19, 2021

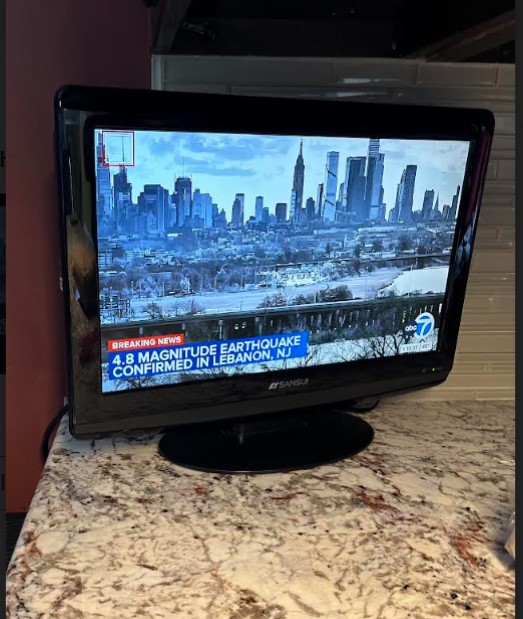

The Amistad curriculum, enacted in New Jersey on August 27, 2002, endeavors to increase awareness of African Americans in U.S. History and develop students’ understanding of different perspectives. But does it do enough to broaden the narrative?

Students in Mr. Terry’s Advanced Placement United States History class noticed that their textbook, The American Pageant, contained leading language and an imbalance of historical narratives.

Words such as “slaves” or “blacks” are used in the textbook, terms that are largely considered outdated for being dehumanizing and politically incorrect. These terms relegate people’s identity to commodities, rather than human beings. Also among these terms were instances where enslaved people were not given a voice, instead of being overshadowed by their more powerful white counterparts.

Another example is a map labelling Africans as “immigrants,” which completely invalidates their history of being forced into slavery in an entirely different continent. Unlike other groups on the map, who had chosen to immigrate to America, Africans had no autonomy in the decision.

“I think the textbooks we use are mostly Eurocentric and depict only one side of history without taking the other perspectives into account. It also downplays many important and traumatic events in history. Overall, I don’t think this textbook should be used,” said Radha Pingle, a sophomore at Hills.

But some students disagree, defending the textbook.

“I think that the American Pageant provides multiple perspectives on situations that other people would not think of. And because of this, it allows people to fully grasp the content, which is educational,” refuted Brandon Huang, another sophomore who uses the textbook.

Journalist Frances Fitzgerald, author of the book America Revised: History Schoolbooks in the Twentieth Century, analyzes the way students engage with history through their textbooks. The book explores historical narratives shaped by politics and shows how, often, history is hardly ever without a bias of some kind.

“The surprise that adults feel in seeing the changes in history text must come from the lingering hope that there is somewhere out there an objective truth. The hope is, of course, foolish. All of us children of the Twentieth Century know, or should know that there are no absolutes in human affairs, and thus there can be no such thing as perfect objectivity,” said Fitzgerald.

So what can be done to expand the narrative?

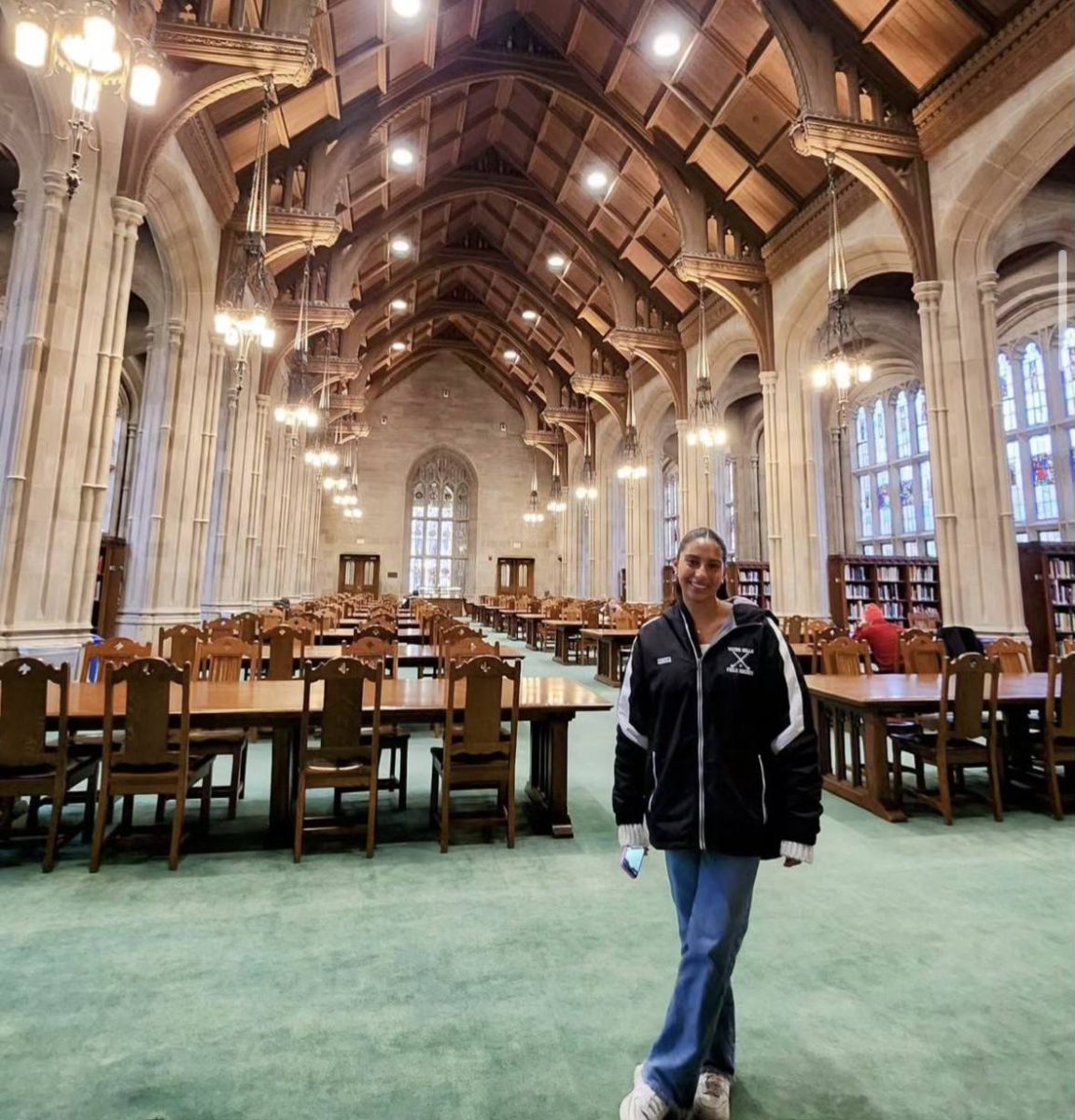

Teachers such as Mr. Terry have taught students to be analytical when receiving information from both primary and secondary sources. When incorrect terminology is used to describe groups of people, teachers can proactively educate students about the history of the word. Primary sources can be examined alongside the textbook to give an accurate representation of the event.

“While a textbook can serve as a general foundation for building basic content knowledge while students engage in a study of history (or another subject in social studies), it is also reasonable and necessary for students to interrogate the way that knowledge is presented with other sources, regardless of who the textbook was written by, or how it was written,” said Mr. Terry.

Most of all, students themselves can be involved to make sure that the content is informative and correct. The young people of America have been at the forefront of political movements. Youth participation in politics means that the next generation is ready to make a change, big or small.

By being critical of the content they engage with, students can make sure that the history they learn is diverse and inclusive.