‘I’ve Felt the Glass Ceiling’: Feminism, and What Advocacy Looks Like on an Everyday-Level

December 23, 2022

“I’ve felt the glass ceiling, and circumstances with misogynistic attitudes or the stereotypes that come with being a woman.”

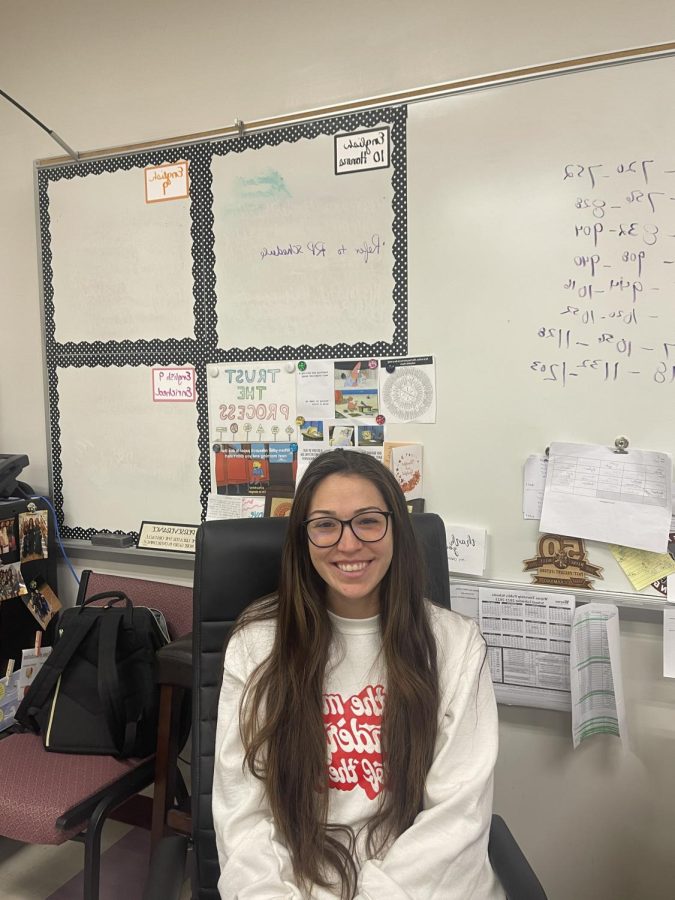

Christina Caamaño, an English teacher at Wayne Hills, has been a pillar of hope for engendering crucial dialogue on feminism while also defining what it means to be an advocate.

At a young age, Caamaño had a predilection for teaching. “Everyone wants to be a movie star when they’re younger, but I just didn’t have the talent,” she joked. She went on to articulate that in realistic terms, she always knew she wanted to be a teacher: a decision grounded in her positive experiences with her teachers growing up. In 10th grade, an A-minus on a paper would be the catalyst for her becoming an English teacher.

Assigned to construct an essay on Tess of the d’Urbervilles by Thomas Hardy – a novel with arduous diction – Caamaño bought a copy, had post-it notes, annotated, and closely analyzed it. Getting the paper back with a positive grade was an intimation of her future career.

“I remember feeling like I can do this, and I can be good at this,” she recalled, “I actually enjoyed writing the paper.” Then, reflecting, she noted that class consolidated her decision to teach, “I want to be like that (teacher). That’s what I want to do.”

After graduating high school, she went to Montclair State University to major in English Education. Her mindset at the time was, “I’m not the best writer, but I’m enthusiastic about it, and I’m more inclined to major in that because I would be willing to do the work for it.” In college, as a part-time job, Ms. Caamaño trained children from ages 4 to 12 in soccer sessions and clinics. She also played soccer for the Montclair women’s soccer team from her sophomore to senior year. Overall, her experience entailed much studying, hanging out with her roommates, and “eating pizza at 1 am with my friends while we procrastinated studying.”

However, during her first semester, Caamaño received a poor grade on one of her papers. “There was red ink everywhere. You couldn’t even see what I wrote – that’s how much this professor marked it.” It made her question if she had made the right decision; nonetheless, she checked the corrections, spoke with the professor, and was ready to improve: until it happened again. Ultimately, “for mental health reasons,” she dropped the class, stating, “I never quit things, and I had to quit something, which was devastating.”

2011 was when Ms. Caamaño would begin her first job: at Wayne Hills High School. She taught mostly sophomores and got more involved with the school as the years passed.

In 2021, amidst a politically reformative social climate, Ms. Caamaño took on the extra responsibility as a club advisor to the Empowerment Club. The club serves to empower all groups of people and defy pre-existing, harmful, and deleterious stereotypes. As a result, she said, “people make time for the things that are important to them.”

Ultimately, she took on this role to give students a voice and a place to learn. She denotes that she sometimes felt like she didn’t have a voice and wanted to provide a space where students did. “It’s been a rewarding experience for me,” elaborating that she has learned much about various cultures and human rights-related issues through the club. Specifically, hearing from students with genuine experiences has positively impacted her, commenting, “It’s making me a better person in the classroom on how I can be there for (my students) and be an advocate for them.”

As an advocate, Caamaño has inextricable ties to feminism. Mainly because of a childhood in a male-dominated space: sports. Despite playing multiple sports, there was an evident lack of female coaches in her life. She only had one female coach, and all the others were male. “She was always such a positive role model, and I remember thinking it was nice to have that because I was so used to being around men and listening to them. So, to have a female athlete in front of me was something to aspire to and look up to.”

At Wayne Hills, Caamaño is the girls’ soccer, fencing, and track coach. During a game, she questioned a call, attempting to advocate for her athletes and fairness. Instead, the referee was dismissive towards her. Then, a male coach went up to the referee, and he was much more responsive. However, there have been positive accolades despite how tiring it might get. “I’m tired all the time. Don’t you see this coffee in my hand,” she joked as she pointed to the large coffee mug in her hand. It’s most challenging preparing for one sport while in the thick of another, she remarked; nevertheless, the award that comes from it is worth it. Caamaño creates “spaces for kids to have somewhere to belong.” Many of the girls learned to fence the day they walked into tryouts, and the same with track. “It’s most rewarding seeing them dedicated to something and learn it, and master it, and that sense of pride that swells in them.”

Young girls must see other women in leadership roles, Caamaño believes. Girls can envision themselves in positions of power because they have seen other women do it. She discusses that last year, she was the only female on the track staff, and she was coaching boys as well. Therefore, it demonstrates to young female athletes that they can lead and lead boys too.

She has been an influential female leader to Wayne Hills students and staff. Sophomore Sophia Flower stated, “She has really encouraged me to become a better writer,” adding that Caamaño had been a positive female role model in her life. She has also been a role model for senior Trisha Vyas – for whom she illuminated that women can be headstrong, and it’s admirable, not something they should apologize for.

Additionally, Caamaño has incorporated feminist teachings in her class throughout the years. For example, while reading The Odyssey by Homer, she has students view the piece from a feminist perspective. In addition, she has students discuss the impact of female characters. Ms. Caamaño cited that the female characters in the book are more of an asset to Odyssey’s journey than the male ones.

Last year, in her sophomore English class, students used the feminist lens using The Scarlet Letter— talking about how the main character, Hester, was commended for the same sin a man committed: adultery.

Furthermore, she asks her students to consider, “How are male characters represented in contrast to female characters? Do texts reinforce stereotypes, do they break stereotypes? Is it an antifeminist piece? Is it a feminist piece?” Through opening conversations on women’s lived experiences through literature – which is imperative to culture and society- Caamaño signifies meaningful change—embodying the very attributes of what it means to be an advocate: enacting feasible actions that could, no matter how small, better the world.

Ms. Ventimiglia, an assistant principal, has watched as Ms. Caamaño got super involved in the school, and “it’s been a pleasure to be a role model and support to all the teachers here, and it’s been really cool to see the growth. Now I’m the old lady. To me it’s what a teacher should be: involved in the classroom, and outside of the classroom.”

In the 2021-2022 school year, Caamaño won the Governor’s Educator of the Year award: feeling like it was all a cumulative moment for all the hard work she has done.

Through her actions – advocating for her students, athletes, and women, Ms. Caamaño, along with other teachers, will reform the world and change younger generations infinitely.

Skyler • Dec 23, 2022 at 11:07 AM

I love hearing about one of my favorite coaches’ opinions on such a crucial topic, mainly because it’s not discussed enough. Thank you Ms. Caamaño!

Lana • Dec 23, 2022 at 9:22 AM

This is a great interview and it is great to see Ms. Caamaño’s perspective on so many topics! She is very inspirational.