New York City Ends Gifted and Talented Programs in Public Schools

October 28, 2021

New York City Mayor Bill de Blasio recently unveiled a plan to phase out the gifted and talented programs in public schools after studies and critics alike have reported the racial divide said programs cause. The mayor said that this year’s G&T programs are the last standing and a more inclusive model of accelerated learning.

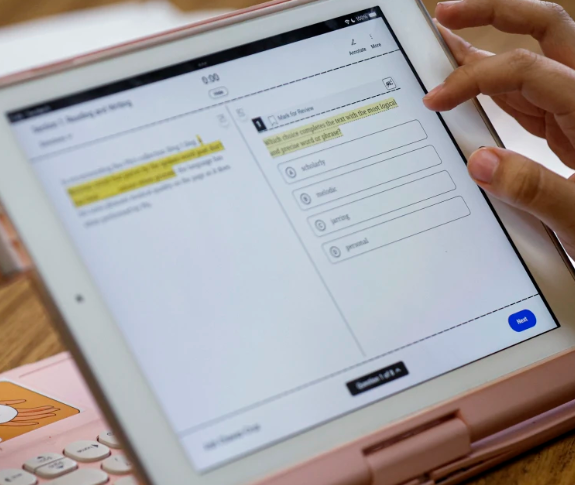

In order to have access to the current G&T program, kindergarteners partake in a high-stakes exam, many of which have families that pay for tutors in preparation. These programs “are considered a crucial stepping stone for students seeking to advance into competitive middle and high schools.” Unfortunately, if a family doesn’t know someone or cannot afford the tutoring, their child is pigeonholed to struggling district schools that receive a lot less attention and money from the government.

Karla Stenius, a parent from Brooklyn, agreed with this statement in an interview with the New York Times. “If we’re just dumping a bunch of resources into gifted and talented,” she said, “everybody else suffers.”

So, what does this all mean going forward? The new learning model is said to include tens of thousands of young kindergarteners, with neither tutoring nor funding from parents required. Under the new plan, the city will train nearly 4,000 kindergarten teachers to accommodate students who need accelerated learning in their general education classrooms. This training could cost tens of millions of dollars, followed by another evaluation once students reach the third grade. This assessment will determine if further higher-level instruction classes are necessary for a subject or two.

Assuming the plan moves forward after receiving feedback from parents and educators, it is possible that other districts across the nation could take on similar approaches. Wayne Schools has a similar current plan, beginning to test kids in the 4th grade to see where they fall intellectually, and if further advanced instruction is required. Little prep-work goes into these tests and students who are accepted into the gifted and talented programs are done so truly based on current/basic knowledge.

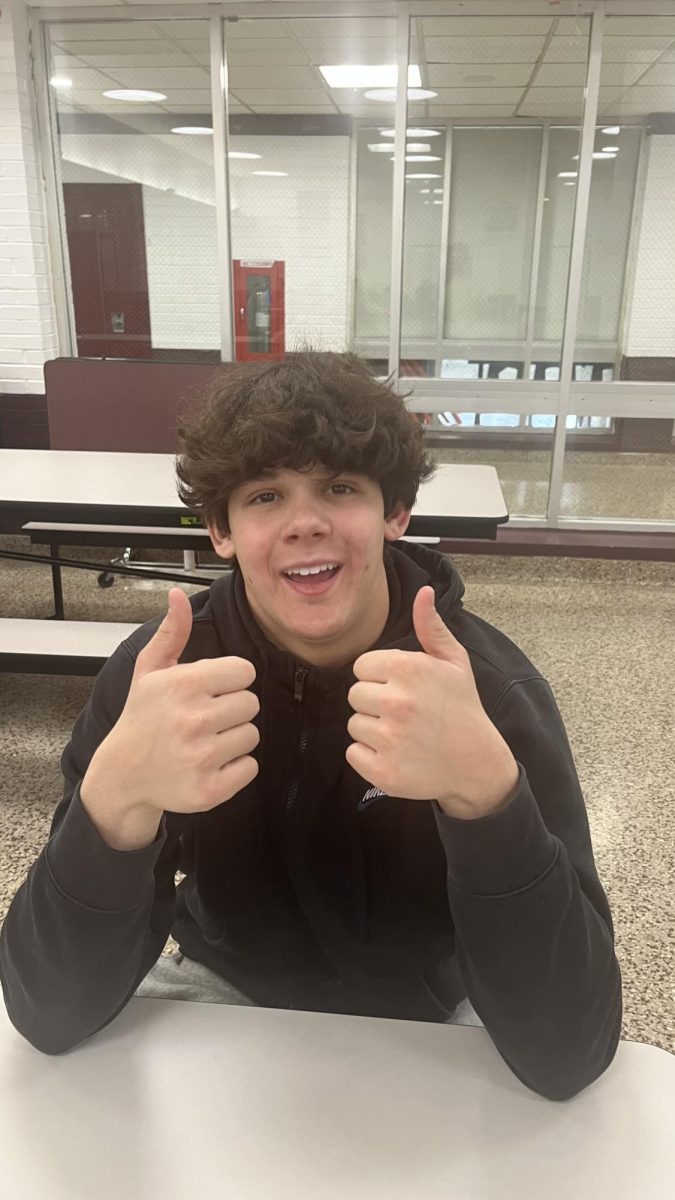

The idea behind De Blasio’s plan is there, but will the execution be up to par? Is it possible for Wayne students of different IQ’s to be put in the same classroom and expect to be accommodated equally? Junior Trisha Vyas says that she does not “think phasing out the gifted and talented program should be a solution because the program is for kids who, without previous tutoring, can excel with accelerated programs. Some children may be faster learners than others and they should be in an environment that gives them the best chance at success. If you were to place both fast and slow learners in the same classroom, it would be difficult for them to learn together at the same pace.”

Although De Blasio is facing his final months in office, the Democratic nominee for mayor and the prohibitive favorite to win next month’s election, Eric Adams, has a similar opinion: these programs need to be altered to become more inclusive. How he decides to go about it may be different, but will be revealed in the following months.