Separate But Not Equal: Entrenched Racial Segregation Is Thriving in New Jersey Schools, Lawsuit Alleges

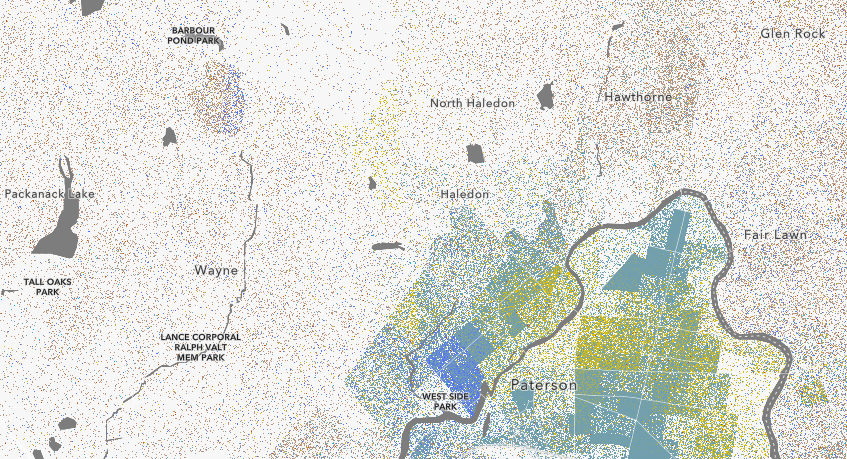

A racial dot map shows racial segregation around Wayne: yellow dots represent black people, light blue Hispanic/Latinos, while brown dots and blue dots show white people | arcgis.com

March 17, 2022

A decade before Brown v. Board of Ed, the New Jersey constitution outlawed overt segregation in schools, so it may shock or horrify some that 75 years later, the state is under renewed scrutiny for the very same problem. A lawsuit filed by a coalition of civil rights groups alleges that racial segregation is alive and well in New Jersey public schools: and it’s up to the state to fix it.

Known as Latino Action Network v. New Jersey, the lawsuit was filed in 2018, but vigorous opposition and legal maneuvering on part of the administration of governor Murphy has bogged the case down and stalled it for years.

The case currently awaits a decision; if the court rules in favor of Latino Action Network, the state of New Jersey will be forced to adopt an official school desegregation plan and immediately take steps towards integrating public schools.

The lawsuit cites research by UCLA which found “severe segregation” in New Jersey schools and warned that New Jersey was looking toward a “segregated future” if there is no change. An analysis of data from 2016-2017 found that New Jersey public schools are the 6th most segregated in the nation.

The numbers don’t lie: looking at demographic data of several New Jersey schools shows extreme racial disparities between neighboring school systems. For example, East Orange school district is nearly 91% black, while nearby Millburn Township is just 5%. Willingboro Township school district is 84% black, while the close Moorestown Township is 6%. A study from the Center on Diversity and Equality in Education found 1/4 of New Jersey schools are “desperately segregated”: where student enrollment is either 90% white or non-white.

Breaking it down by race shows just how severe the problem is. 40% of white students attend schools more than 75% white, 62% of Latino students attend institutions that are more than 75% non-white, and 25% of black students in New Jersey go to schools which are, staggeringly, more than 99% non-white.

This revelation may be surprising to some, as New Jersey is one of the most racially diverse states in the country and is considered to be progressive in policy. However, studies have repeatedly shown that so-called de-facto racial segregation in public school systems has consistently been the worst in Northeastern states such as New Jersey and Massachusetts.

“The idea that New Jersey, a modern, progressive state in the Northeast should have such segregated schools was horrifying”, said Gary Stein, a retired Supreme Court justice.

Lawrence Lustberg, an attorney for the plaintiffs, said,”It is about racial justice in a state that congratulates itself on being fair and just and egalitarian, but is in fact among the worst in the nation when it comes to the segregation of our public schools.”

Out of all the public school systems in New Jersey, three counties were found to have the worst and most extreme racial segregation, all in the northeast of the state. The counties were Essex, Union, and Wayne Hills’ very own Passaic County.

Sean Kim, a senior at Wayne Hills High School, said, “I think because Wayne, New Jersey is a predominantly white town, there is bound to be racial segregation within school systems. However, looking at it objectively, I can say it is probably a problem.”

Wayne Township Public Schools present a perfect example of the extreme de-facto segregation present in Passaic county. According to Niche.com, Wayne schools are more than 71% white, while neighboring Paterson Public schools are almost 90% non-white.

This reflects a clear trend in wider New Jersey: predominantly poor urban school districts surrounded by wealthy, majority-white schools. In court, the state of New Jersey uses this fact to defend the rampant segregation present in schools. They contend that the plaintiffs in Latino Action Network vs. New Jersey are using “a small sample of raw demographic data“ that is simply reflective of housing choices, rather than proving evidence of segregation.

Some say the state is feigning ignorance, and the plaintiffs argue that , “analysis demands an understanding of a variety of factors. It demands an analysis of access to affordable housing and transportation and other socioeconomic factors.”

In northeastern New Jersey specifically, historic segregation practices, such as redlining, in which minorities were discouraged from buying homes in white neighborhoods, and blockbusting, which encouraged “white flight” from New Jersey’s urban centers, have created deeply entrenched segregated communities which have persisted despite the legal prohibition on racial segregation practices.

One policy frequently critiqued by supporters of the lawsuit is the New Jersey state law which requires students to attend school in the districts of their residence. This prevents integration between neighboring communities with vastly different racial demographics.

Plaintiffs say that the state of New Jersey is effectively saying that the doctrine of “separate but equal” is valid by denying there is segregation present in schools: Brown vs. Board of Education, the lawsuit that brought down legal segregation, explicitly condemned the idea of separate but equal, which was used to uphold racial segregation in schools in the past.

Segregated school districts are not necessarily equal either. There is an extreme racial wealth gap in New Jersey. The median wealth for white families is a staggering $322,500. The median wealth of black families? A measly $6,100. Income is also unequal – white families in in New Jersey have an average per capita income of $54,704, while black families earn a little less than $30,000 on average. Proponents of the lawsuit note that the way in which New Jersey schools are funded, with local tax revenue, creates well-funded and robust educational institutions in historically richer, white neighborhoods. In contrast, majority-minority school districts, mainly located in urban centers or other poor areas, are left with little in the way of funding. The state of New Jersey does provide aid to underfunded schools, but some say it’s not enough.

This can seriously effect the educational outcome of students in these districts. For reference, Wayne Township Public Schools spends about $21,839 per pupil, while Paterson Public schools spend $17,592; the average SAT in Wayne Schools is 1230, while in Paterson it is a 970.

There are social benefits to attending a diverse school as well. Christopher Weber, the deputy attorney general, said, “The importance of attending a diverse school environment cannot be overstated … the experience of being immersed in a racially and socioeconomically diverse school is … critical ingredient in the life of every child … innumerable benefits of exposure to different racial, cultural, and socioeconomic backgrounds, and acknowledges that there is unquestionably room to improve the current system.”

Rahaf Al-Sattari, a junior at Wayne Hills High School, spoke on attending a “non-diverse” school, saying, “I’m definitely marginalized as an immigrant [at Wayne Hills] … I often feel I am not taken seriously.”

What can be done to integrate New Jersey public schools? Proposed solutions include redistricting communities or allowing students to attend school in neighboring school districts.

A new bill was approved by the Senate Education Committee of New Jersey which proposed creating a Division of School Desegregation within the state education department to examine ways to expand school integration in the state of New Jersey.

The extent to which Wayne Hills High School may be affected by the lawsuit and suggested desegregation methods is not yet understood, however, Wayne Hills exists in a highly segregated county of New Jersey, and may be affected by future desegregation efforts.