Canada’s Historic Settlement With Its Indigenous Peoples

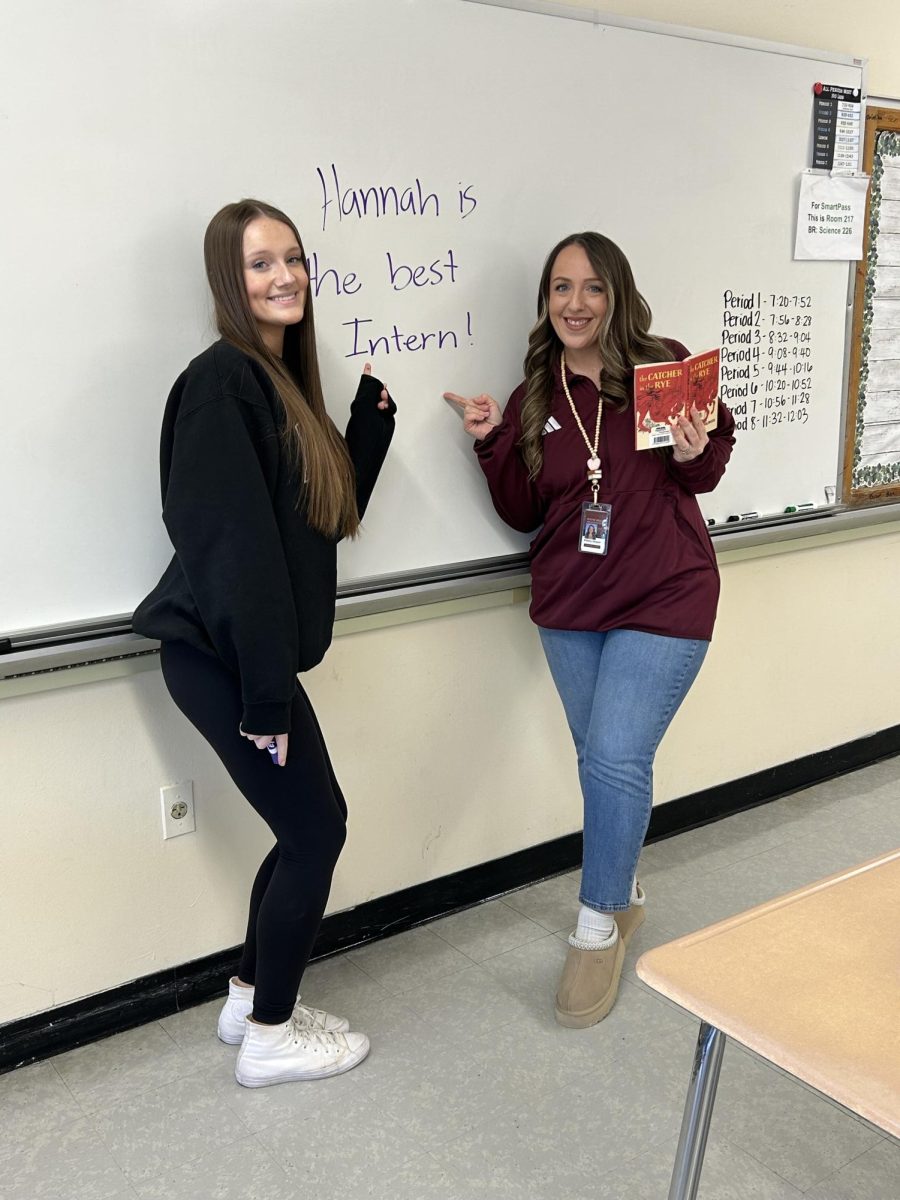

Kamloops residents and First Nations people gather at a memorial in front of the former Kamloops Indian Residential School after the remains of 215 children were found at the site.

February 15, 2022

Canada has a history of human rights violations regarding its indigenous peoples. More than 150,000 children were taken from their homes and sent to residential schools between 1883 and 1997. 90 to 100% suffered serve physical, emotional, and sexual abuse. The goal of the school system was ultimately cultural assimilation.

The prime minister at the time, Sir John A. Macdonald, said in 1883 that the goal of the schools was to quote, “‘Acquire the habits and modes of thought of white men.”’ Indigenous children were forced to engage in manual labor, prohibited to speak their languages, and were forced into religious instruction.

John Jones, a residential school survivor, describes his personal experience at one of the residential schools. “‘The physical abuse was every day,'” he says. “‘And being assaulted verbally — if I didn’t do things the way that they wanted me to do, I was called a dirty, stupid Indian that would be good for nothing.'” There’s a lot on record from different politicians at the time agreeing that this was an appropriate way to handle the “problem.”

This is substantiated by a 2015 report from Canada’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission that cites Duncan Campbell Scott, who ran the schools from 1913 to 1932. Campbell said in 1920, “‘I want to get rid of the Indian problem. I do not think that the country ought to continuously protect a class of people who are unable to stand alone. Our objective is to continue until there is not a single Indian in Canada that has not been absorbed into the body politic.'”

There is a clear problem here on a systemic level. With Indigenous children making up less than 8% of children under the age of 15, they account for more than half of all kids in foster care, according to 2016 Canadian census data. When interviewed many Indigenous peoples go on to express the lingering effects that these schools left on them; furthermore, the huge impact it left on their ability to parent their children. They were subjected to rigid and harsh living conditions without any affection or words of affirmation. So the impact goes beyond the experiences they dealt with at the schools, but it affected them for the rest of their lives, and then their kids’ too.

During the 1980s the schools started to phase out; nevertheless, kids were still being taken from their families but in a different way. Many children living in Indigenous communities were shown in the foster care system. Besides the multigenerational trauma that affected the ability to parent, there was also a lack of funding on a federal level. Most child welfare services in Canada are funded by provinces, except services on Indigenous reserves are funded by the federal government.

Cindy Blackstock, a member of the Gitxsan First Nation, the executive director of the First Nations Child and Family Caring Society of Canada, and a professor at McGill University says, “‘Canada continues to treat First Nations people as if they are not worth the money by providing deficient public services on reserves and choosing to not implement solutions.'” Blackstock expresses that this is a quote “part of a larger issue.” The issue is that the problems that may result in kids being put in the foster care system are not being addressed.

In the early 2000s, Cindy Blackstock became the Executive Director of an advocacy group called the First Nations Child and Family Caring Society, and in 2007, she and her organization partnered with another group to file a complaint to the Canadian Human Rights Commission. The complaint states that there was an inequity in the funding spent on child welfare services compared to the rest of the country. There were legal battles that spanned many years. But last year, a story from British Columbia came out about the residential schools that changed the public’s view on the case.

In the story, reports found that more than 200 children have been found and buried on the site of a former residential school. Hearing about the unmarked graves completely shifted the perception of the relationship between the Canadian government and its Indigenous peoples.

On January 4th, the government announced its largest settlement after several lawsuits brought by First Nation groups. It is a payment plan to compensate Indigenous families whose children were taken from their homes by Canada’s child welfare system at a disproportionate rate. Using $32 billion, roughly half the money will go to kids and their families who were wrongly pulled into the foster care system, or who received inadequate services on reserves.

Junior Riya Kachroo says, “When it comes to historic injustices there must be historic reparations. Governments need to take responsibility for their part in systemic injustice and I believe what Canada is doing is great. But throughout the years we hear a lot of government promises. So I hope to see that this money changes things.”

The future is bright for the indigenous peoples in Canada today; however, it’s important that the people and residents of Canada hold their country accountable. The only way we’ll know if the money has made actual change is if we see a lower number of indigenous children in the foster care system.

Hanna Hajdu • Feb 16, 2022 at 8:07 AM

This was an amazing explanation of the issue. This topic is definitely not brought up often, so it’s great to have articles like this to inform students.